The following is a repost of a Facebook post done Tom Horning, a geologist and city councilor, who lives in Seaside, Oregon and has been a long time advocate for preparing for a Cascadia earthquake and tsunami. He granted me permission to get it out to a wider audience:

The GREAT AMERICAN SHAKEOUT occurred in Seaside at 10:18 AM. A few seconds of modest seismic shaking was followed by 3 to 5 minutes of violent wracking that knocked the terracotta roofing off of City Hall and collapsed the brick bell tower of the fire station onto the fire trucks in their parking bays.

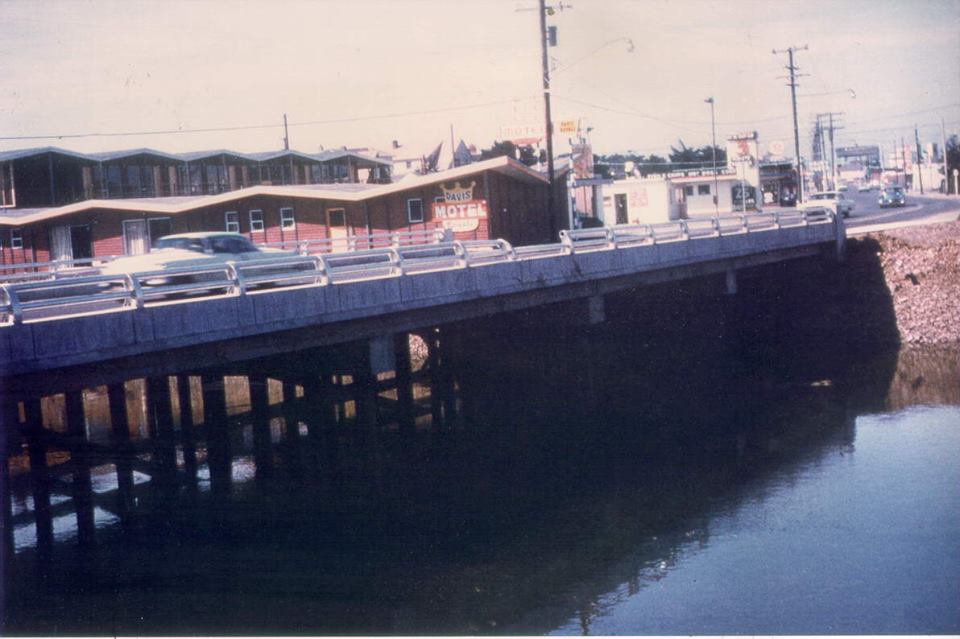

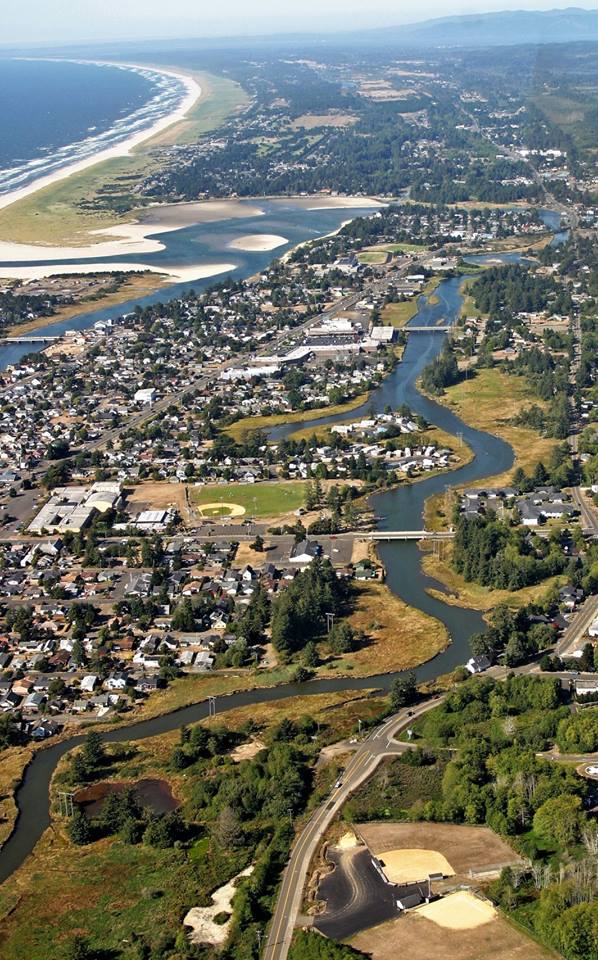

Seven of eleven bridges in Seaside collapsed when the soils liquefied during the shaking, preventing panicked crowds of tourists and locals alike seeking safe evacuation routes. A few young people swam the rivers or picked their way over the shattered concrete to safety. Four bridges that had been replaced around 2002 withstood the shaking and provided safe and timely evacuation, although areas with riverbank fill spread laterally, rupturing several streets and further delaying evacuation.

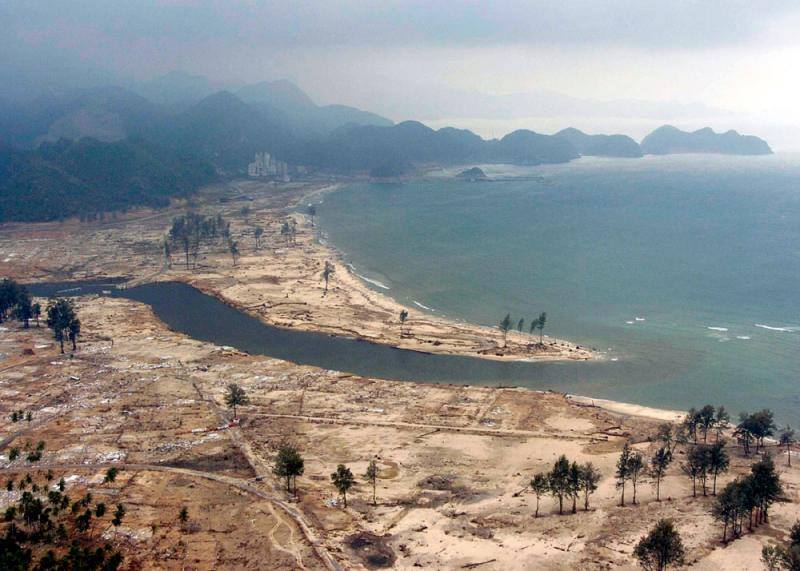

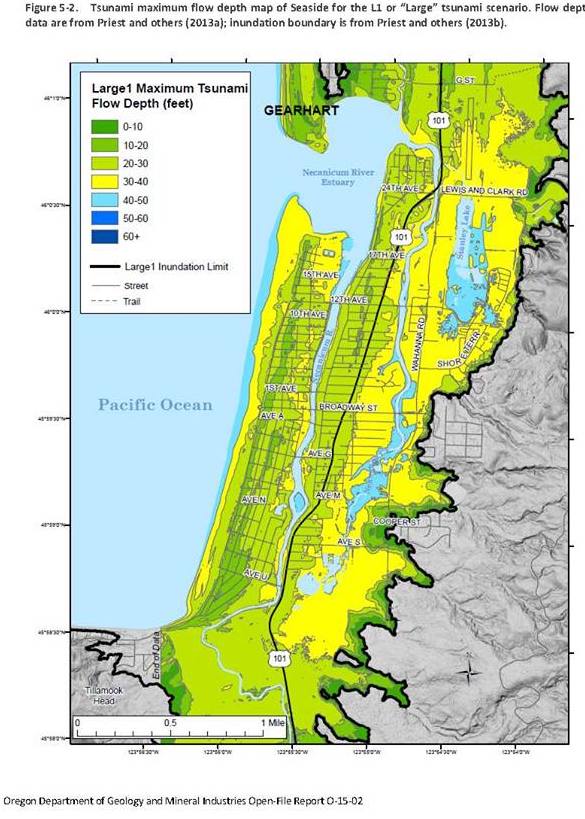

Fifteen minutes after the shaking ended, the predicted tsunami began creeping up the beaches. By twenty minutes, seawater was flowing over the Prom. By thirty-five minutes, water was roaring through

the third story windows of motels on the Prom, in buildings that did not collapse from the shaking.

Flood waters were 40 ft deep at Highway 101 and Broadway. Ninety percent of the houses and buildings in Seaside were destroyed by the first surge of the tsunami. Much of the debris floated out to sea as the tsunami withdrew but returned violently with the next surge, knocking the remaining structures down and killing people who took refuge in masses of floating debris.

Documented fatalities for Seaside and Gearhart totaled 3,927 souls, mostly elderly, the very young, and visitors. Of these, about forty percent of the citizens in Seaside were killed, largely because of the lack of safe evacuation bridges. The primary cause of death was drowning, although many people died after the disaster due to crush and impact wounds, sea water ingestion, and hypothermia. The total loss of life was nearly three times that of Hurricane Katrina and more than those killed in the World Trade Center collapse. The totals could have been many times higher had the earthquake struck during summertime.

Only about 15 percent of Gearhart citizens died, the number limited by easy evacuation access to the high dune in the west part of the city. However, many suffered from hypothermia because house fires consumed many of the surviving buildings in the west dunes, exposing them to rain. Fire and emergency medical equipment were ruined by salt water immersion, because the old station had not been relocated to high ground, as advocated by city staff and a citizen’s committee. Similar fires spread through the Sunset Hills neighborhood of Seaside. Fortunately, the nearby new school complex was able to house the refugees and offset the effects of weather and low nighttime temperatures.

The coast was isolated for several weeks, as the nation mobilized to render assistance. The coast suffered the worst loss of life of all communities in the Cascadia region. Clean water and food, sanitation, and medical supplies were in short supply. Surviving homes were used to house survivors under difficult circumstances. Seaside and Gearhart suffered more than $1.2 billion in lost real estate values. Damage to utilities is still being evaluated, but it is likely that the entire infrastructure will need replacement.

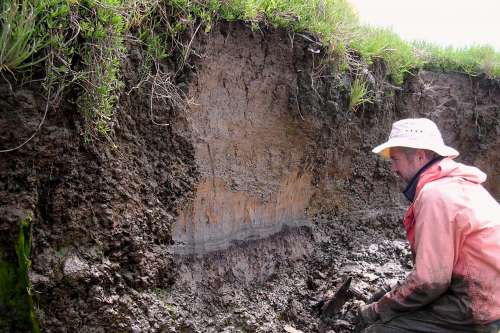

As expected from several decades of research, the tsunami left sheets of sand in the marshes and forest as evidence of the flooding, whereas vertical changes in land elevations, totaling 5 ft, caused shoreline forests to drop below wave base and die from saltwater poisoning. Local beaches and dunes have washed away, the shoreline retreating nearly 800 ft eastward as ocean processes redistribute sand into seafloor depressions created by changes in land elevations. During the 5 minutes of shaking, the land rebounded elastically to the southwest by as much as 55 ft.

Claims of malfeasance and ineptitude against community leaders have been leveled by families of survivors. Efforts to fund the construction of new bridges with room tax increases were opposed by the lodging industry. Few sources of other funding had been appropriated by state or federal agencies for hardening coastal infrastructure. Delays in delivering assistance have been significant. Many additional deaths from injuries and lack of appropriate medicine have occurred. Most agree that it may be several years before the cities can begin to rebuild. All agree that the coastal communities should have been better prepared.